The iconic North American monarch butterfly Danaus plexippus plexippus was recently listed in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, signalling that its ongoing decline could lead to extinction. The compounding effects of habitat degradation, insufficient food and water and climate change have led to these dwindling numbers.

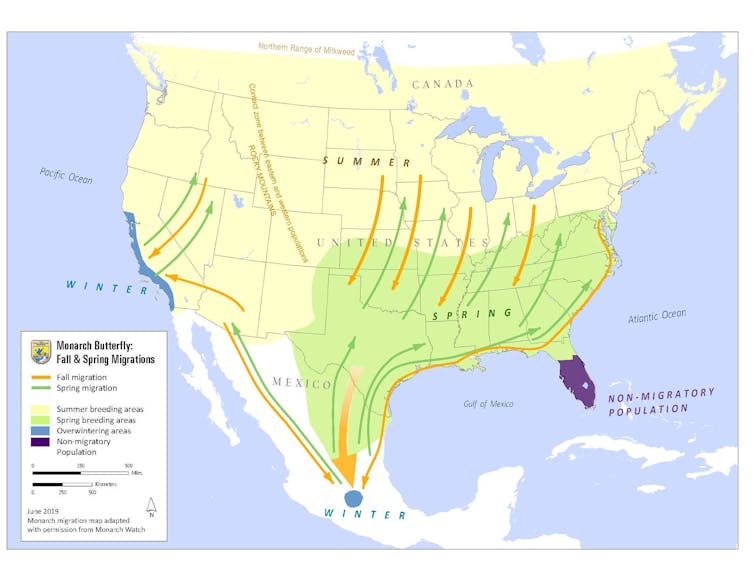

This tiny, almost weightless, butterfly can travel thousands of kilometres across natural and human-made borders with ease. It can survive harsh weather during its long-distance flights across Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. And it has developed, over millennia, these movements in a delicate relationship with its milkweed host plant.

Despite their remarkable adaptations and ongoing conservation efforts, things have gone downhill for these monarchs. Why? Part of the answer lies in our misguided approach to protecting them.

As a social anthropologist, I have followed this butterfly across North America over the past decade. I document how monarchs are natural crossers, uniting people, fields of expertise and countries. What is at risk of disappearing with them, I argue, is the wonder of a natural connector. And we need to unite to truly protect them.

Monarch butterflies need people

Most monarch conservation initiatives are grounded in a false separation of nature and society. Monarch conservation reserves are based on a western ideal of pristine nature, fenced off from humans.

National parks that protect monarchs removed — sometimes forcefully — local people, including Indigenous groups who have long lived sustainably with these insects. This separation caused the monarchs to suffer from that disconnection from the communities which followed agricultural practices that protected them.

(Shutterstock)

In Mexico, forest extensions that used to be community commons (later a Biosphere Reserve to protect monarchs) have been converted into avocado plantations. In Canada, the emblematic Point Pelee National Park that hosts monarchs at their fall migration also substituted monarch habitat with wooded areas that are not suitable for monarchs. Creating this National Park entailed evicting the Caldwell First Nation from their ancestral land.

Borders affect monarch conservation

Monarchs are negatively affected by national borders. The U.S., Canada and Mexico have different environmental laws and political priorities.

Monarchs are protected when they spend the winter in the cool and humid forests of central Mexico, but the migratory route is still not fully integrated into the conservation plan. In Canada, monarchs are listed as endangered but protected differently across provinces and in the United States, monarchs are still not listed as endangered.

These protective measures keep changing and political and economic motivations can take precedence over the genuine need to care for monarch habitat trans-nationally. For example, a butterfly enthusiast can freely collect and rear monarchs in captivity in most of the U.S., but not in Ontario.

(USFWS Midwest Region/flickr)

Monocrop displaces milkweed and monarchs

Monarchs live in an unequal North America — a region that is integrated economically and geographically, but marked by inequality based on race, class and citizenship. The fates of marginalized residents are closely tied to those of the monarch.

This is seen in monocrop agriculture, which has displaced Indigenous people and destroyed habitats for monarchs and other pollinators by changing the native landscape.

Meanwhile, agribusiness, which is both a push and pull factor in the precarious migration of Mexican farmers, has also displaced the milkweed in what is known as the Canadian and U.S. corn belt.

Rethinking conservation strategies

Monarchs’ migrating behaviour entails crossing nature and human-made barriers despite the added difficulties of this journey.

Instead of more fragmentation and boundaries (around countries, parks and people), what monarchs need to survive is for us to emulate their “crossing” behaviour. We must ask: how can we create more and better crossings?

(Howard County Library System/flickr), CC BY-ND

To enable more crossings, we need to de-centre the role of conservation experts as leaders of monarch protection policies. Actions to save the monarch butterfly should be planned with — not merely in consultation with — Indigenous peoples who have ancestrally lived with this insect.

We also need to begin democratizing monarch knowledge. This would include accounting for the role of citizen scientists in monarch protection. They should be viewed not merely as amateurs or “helpers” in scientific research, but as knowledge producers and, ideally, policy-makers in their own right.

Despite the harsh reality of its path to extinction, we should see the latest monarch listing as an opportunity. We have a short, but potential window to redirect our conservation efforts by connecting crossing fields and boundaries to ensure the survival of this insect and, perhaps, secure a better future for us as well.

We need to move beyond the goal of saving a beloved butterfly to learning from it about how to safeguard our collective futures.